[ 7 ]

Defining the Setting and Context of Your Product

Once Doesn’t Mean Always

In 2014 I went to the Swedish Embassy in London to vote in the election back home. It was one of those moments where I wanted to share my check-in with the world—or in this case, the Twittersphere. I opened up Foursquare, as it was still called back then, added a comment, and tapped the Twitter icon on the check-in screen and checked in.

A few days later, I was on my way to Berlin to speak at a conference and, as usual, I checked in to Heathrow T5 on Foursquare. We boarded the plane, and as I scrolled through my Twitter feed, I saw that Foursquare had shared my check-in on Twitter. I quickly deleted the tweet and opened up Foursquare to see what had happened. It turned out that since that time at the Swedish Embassy, where I’d chosen to share my check-in, sharing check-ins was now turned on by default.

It may seem like a small and silly thing, but these little things really make a difference. As the world we live in, and design for, becomes ever more filled with noise, it’s our responsibility as designers to make sure that we don’t add to it unnecessarily but instead help users do what they want and not make assumptions or decide for them. The right and nice way for the Foursquare app to have behaved in this instance would have been to look at my past behavior in the app and use a simple algorithm to decide how to handle the check-in scenario. As a rule of thumb, apps should not change the default behavior and setting unless the user has specifically asked for it—and definitely not without telling them.

If Foursquare had analyzed my behavior in its app, it would have noticed that I very seldom share my check-ins. As a result, the default assumption of the app should have been that if I share a check-in, it’s probably a one-off or a special occasion. However, if I’d also chosen to share my next check-in, and the check-in after that, the start of a pattern would have been established, which Foursquare could have confirmed by asking if I’d like to change the default setting to share all check-ins on Twitter.

Because technology increasingly takes the form of useful assistants, this is a simple example of an opportunity to nudge users with a friendly “Hey, we noticed that… Would you like to…?” style of communication. These simple if-then scenarios, otherwise known as conditional statements, can be quickly mapped through a decision tree or user flow, and it’s both in the user’s and Foursquare’s interest to do so. When we design experiences, we should always strive to do that which will provide the user with a positive one.

Accidentally sharing every single Foursquare check-in can make you feel like a fool, and it also creates spam. Unintentional shares provide very little value, and it’s likely that sharing every single check-in on Twitter isn’t actually in Foursquare’s interest. A check-in without an accompanying comment is pretty much just useless noise, and the small value it can provide in brand awareness is far outweighed by the negative response many users have to this kind of spam broadcast. Not all check-ins are created equal.

To understand what creates and drives value and what doesn’t for both users and the business, we need to look into context and the reason(s) behind the action(s), or lack thereof. In the case of Foursquare, it’s important to understand why people check in and why people share check-ins so it can try to leverage those aspects that drive value for the user, other users, not yet users, and for Foursquare. Foursquare could make and quickly validate a range of hypotheses, from how to identify social moments to how to measure how active a sharer a user is in general.

Personally, I used to use Foursquare as a way to remember certain places I’ve gone to, or times I’ve been there, as well as to log what I’ve done. While writing this, it was helpful to be able to look at when I checked in at the embassy and just how many days later I flew to Berlin. However, I generally don’t want to share those updates, even inside Foursquare. With a simple decision tree, Foursquare should be able to identify, and make sure, that I don’t accidentally share something I don’t want to share. Figure 7-1 shows another example of a check-in I accidentally shared on Twitter after deliberately having shared, and added a comment, to my check-in prior to that about landing at Copenhagen Airport and being home.

Figure 7-1

Another example of a check-in I accidentally shared on Twitter

Understanding all of these parameters comes down to context, which is one of the most powerful and important aspects we have at our disposal as UX designers and product owners. Through context, we have the ability to ensure that we deliver value at the right time, in the right way, and on the right device. This also applies to trying to anticipate users’ needs before they themselves have realized they have them. Context can be used to create products that seem to know you, not in a creepy way, but in a helpful and friendly way of being one step ahead and there when the need arises.

For a long time, I’ve advocated that we should design with the individual in mind. Most of the time, this suggestion is met with some skepticism, just as when you talk through something that’s fairly complex: “It’s too complex. Keep it simple. Don’t design for everyone. Focus on our key audience groups.” But my passion lies in the complete opposite direction. It lies in digging into the complexities to find the simple little things, and the big ones, that will really make a difference and to truly understand how a specific individual might want to use a product or service, and what will really make a difference to them, specifically, not to everyone as a whole. This is where context plays a crucial role and where you need to go into detail and look at the complexities of it all to really find the thing that will make a difference.

The Role of Setting and Context in Storytelling

In traditional storytelling, the setting, or place, is one of the main elements, together with plot and characters,1 whereas context is often talked about in the interpretation of literary works or films. However, that is not the type of context we’re talking about here. We’re talking about context in relation to how to create and tell a story to an audience.

Merriam-Webster defines context as “the parts of a discourse that surround a word or passage and can throw light on its meaning” or “the interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs [namely] environment, setting.” Julien Samson explains for The Writing Cooperative that context is a tool that helps authors build trust and interest with their readers. Context, as Merriam-Webster defines it, can be anything that helps give a story meaning, or that is related to the environment or setting in which the story takes place. Here are some examples of context in traditional storytelling:2

- The backstory

- Details about your character

- An event or situation

- A memory

- An anecdote

- An environment or setting

Context, in other words, serves to ensure that the story works, that the reader or audience understands the “why” of characters’ actions or events that take place, and that a relationship is formed with the reader or audience by creating meaning and empathy for the characters and the plot. Context also helps push the story forward and is an integral part of the story itself, and the telling of that story.

The Role of Setting and Context in Product Design

Before social media, we didn’t have to worry or think as much about the environment in which our website would be used. We knew that users would be sitting in front of a computer, most likely a stationary one, and that they’d use a mouse to interact with what they saw on the screen. Fast-forward to today, and we can’t be sure of anything except that how, where, and when our users will use our product or service will vary. There is no one size fits all, and no two journeys are the same.

With this in mind, coupled with often tight schedules and budgets, it’s easy to think that the need to really work through the bigger picture and the detail is less important. The journey will vary so much from user to user, so what’s the point? However, it’s more important than ever to make sure that we have an understanding of the full end-to-end experience as well as the small contextual details that make a difference along the way. Here the setting and context of the experience play a big part.

In Chapter 5, we talked about acts, sequences, scenes, and shots as a metaphor for thinking through the bigger picture and the smaller details in product design and defined them as follows:

Acts

The beginning, middle, and end of an experience

Sequences

Life-cycle stages or key user journeys, depending on what you work with

Scenes

Steps or main steps in a journey or pages/views

Shots

Elements of a page/view or detailed steps of a journey

When we talk of setting we’ll be using the preceding list as a reference and defining setting as the environment and context in which the product experience takes place.

This is slightly broader than the definition of setting in traditional storytelling, as that’s primarily focused on time and geographic location. What makes for a nice parallel, however, is that setting is at times referred to as story world, and that is very much one of the aspects we increasingly need to include as part of the product experiences that we design.

A Look at Context in Product Design

As Samson so eloquently put it, context is about the relationship between the reader and the writer. In Chapter 1, we talked about purposeful stories; that is, stories created with a specific purpose in mind. In product design, all parts of the experience should be purposeful, from the overarching aim of the experience to the smaller aspects related to individual user journeys.

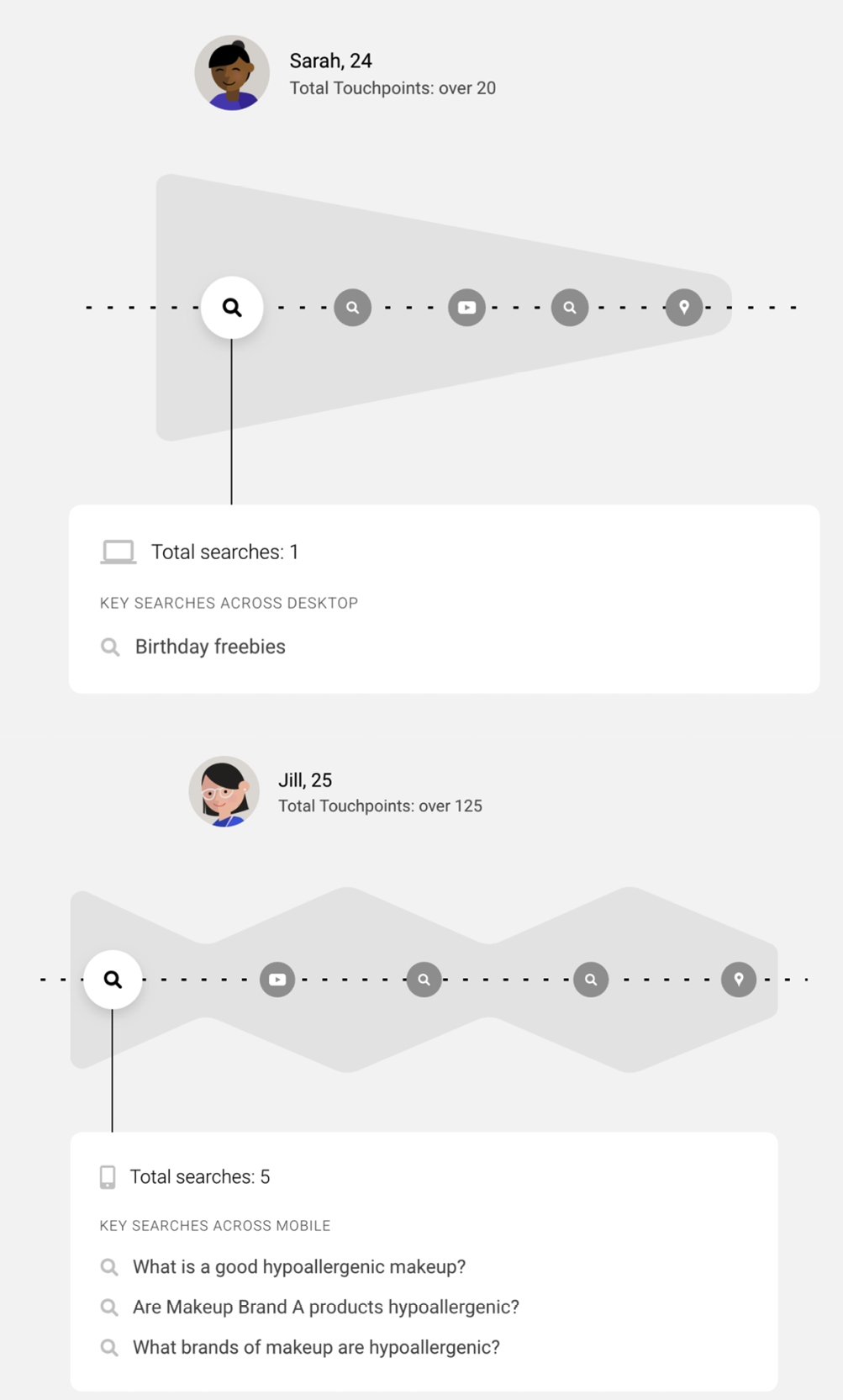

Between September 2017 and February 2018, Google looked at the clickstream data from thousands of users as part of an opt-in panel related to the marketing funnel. What Google found was that no two user journeys were the same. In fact, even when the user journeys took place within the same category, they took different shapes. Traditionally, we’ve been thinking that a user’s search starts wide and then narrows down, and in some instances it does. But in other instances, it widens and narrows, widens and narrows, as shown in Figure 7-2. It all depends.

These types of patterns aren’t just typical for purchase-related journeys. They illustrate how users in general behave both online and offline. Entry and exit points vary, as do the touch points, including how many, that the user comes in contact with along the way.

What we’ve experienced with the rise of mobile technologies, and still are experiencing, is similar to what happened after the introduction of the printing press in 1440. Before the rise of print, a storyteller had a fair bit of control over how their story was told, as the storyteller was typically the one who told the story. Since the invention of writing, but with the rise of print in particular, stories have been able to travel, not just through the storyteller, but through the medium in which they were experienced. Mass communication and the printing press meant that stories could be enjoyed and experienced by many more people, in a various places and contexts—not just the specific ones that the storyteller was in for that storytelling performance.

Figure 7-2

Think with Google user search journeys for a candy bar, where even the smaller details related to the search are verified (top), and a makeup journey, where the user is searching for the best brand (bottom) (https://oreil.ly/G50oO)

Today social media plays a primary role in ensuring that stories, in whatever format, travel. But we also see people consuming more traditional stories in what would previously be considered new environments. It’s not uncommon in many cities to see fellow commuters binging on the latest Netflix series on their way to and from work.

And just as we can jump straight into a later episode on Netflix and skip the beginning, the users of our products and services can land right smack in the middle of a user experience, rather than at page 1, otherwise known as the home page. Additionally, the way users end up on our product or service in the first place is often through search or social media. Rather than being taken to the home page, where the carefully crafted background for the user is presented, they’ll click a link, and whatever accompanies that link is often what provides the contextual backstory for them.

It’s been a good few years since users needed to be at home, at work, or in school to experience the web. At the time of writing, we’re seeing an increasing shift in the way people search. As covered in Chapter 3, users are increasingly expecting results that work for them, at that location and point in time. They’re expecting contextual search results and contextual products and services. To meet their needs in the best possible way, designing for context is crucial.

A Definition of Contextual Products and Context-Aware Computing

Ami Ben David, co-founder and CEO of Owner, defines context for product design as “A contextual product understands the full story around a human experience, in order to bring users exactly what they want, with minimal interaction.”3

In The Grand Budapest Hotel, the new lobby boy is asked to “anticipate the client’s needs before the needs are needed”—and Ben David says that this is exactly what we mean when we talk about context with regard to our users. There is no need to wait for them to ask a question. Instead, we should just deliver what they want, before they know they want it. Ben David goes on to suggest that when we typically think about user interface design, we think about user-initiated interactions: a user makes a request, and the system or service responds. With contextual products, he argues, the user never has to tell the system. The system just knows. That’s the kind of experiences we have the ability to create when we focus on context in multidevice design.

The History of Context-Aware Computing

In the early days of mobile computing, back in the ’80s and ’90s, the focus was on making mobility transparent for the user and automatically making the same service available everywhere. In this case, transparent meant that users wouldn’t need to worry or care about the changes in their environment, but could rely on accessing the same functionality, regardless of their location.

Research into ubiquitous computing that took place at Xerox PARC in the early ’90s caused a shift in thinking, and researchers started to discover the potential of exploiting the context of use for how systems could be adapted. In 1994 Bill Schilit, who introduced context-aware computing, described it as follows:

The basic idea is that mobile devices can provide different services in different contexts – where context is strongly related to the location of a device.4

Context-Aware Computing Today

To this day, we still often think of location when we think about context, but it’s increasingly about much more as well. The more technology is embedded into our surroundings and everyday lives, moving beyond the screen and into objects in our home as well as encompassing more and more services talking to each other, the more complex context becomes. The things we interact with and the ways we do so expand into new areas. In addition, the products and services as well as devices that we use will increasingly have access to rich contextual information about us—from where we are, and indeed, our physical location, to social, health, and other data via sensors.

There’s a tremendous opportunity, not the least to do good, that can come from incorporating this kind of data into the products and services we design. Through the intelligent and ethical use of data, we’ll be able to offer personalization at scale in the form of one-to-one experiences that are tailored to the individual. No more unnecessary noise, or stating the obvious. Just the right content at the right time, for specific users.

In many of the films we see that take place in the future, the protagonist lives in a world full of data. In Minority Report, the machines know everything about Tom Cruise, and as he walks down the streets, he is surrounded by billboards that target him with ads. Digital designer and leaderhsip coach Tutti Taygerly argues that in many movies, such as Minority Report, the interfaces that we see leave much to be desired as the burden of attention and the effort involved with controlling these interfaces is on the user. Taygerly compares Minority Report to the movie Her, where the interface between the protagonist and the operating system is so seamless and so natural that he in fact falls in love with it. Rather than overwhelm, the machine complements the human by being aware of everything, and based on this contextual awareness, it provides relevant suggestions.5

Larry Page of Google shows a video of a man in Kenya, Zack Matere, who says “information is powerful, but it’s how we use it that will define us.”6 Besides making sure that we use the data responsibly and ethically, the power in using data and what we know about users doesn’t just lie in showing them tailored recommendations of content, including products we know they’re more inclined to like and buy. It also lies in how we can tailor interfaces over time through progressive content and progressive reduction. Through clever use of technology, we’re able to deliver a bit of everyday magic. But for that to happen, the system behind the experience needs to know what matters, and when. Only then can we deliver the kind of experiences that anticipate users’ needs before they are there, just like the lobby boy in The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Working Through the Context

Context impacts everything across every stage of the product or service life cycle, and its effect is not limited to digital products. In “Emotion and Design: Attractive Things Work Better,” Don Norman talks about his three teapots and when he tends to use which one. First thing in the morning, efficiency trumps everything else, which results in him using his Japanese hot pot and a little metal brewing ball. At other more leisurely times, or when with guests or family, he uses one of the other ones and says, “Design matters, but which design is preferable depends upon the occasion, the context, and above all, upon my mood.”7

Context is essentially about considering the humans that are about to use or already are using our product or service and taking into account what matters to them, how we can remove obstacles, barriers, and worries so that we help them best meet their needs and goals. Just as humans are complex, so too is understanding context, but that is good. As Page Laubheimer, a UX specialist with Nielsen Norman Group, writes:

When we’re doing our day-to-day design work, we rarely consider our users’ real context. We often assume that people who use our product will be focused on it, with no distractions. But that’s simply not how people interact with digital products.8

Context often plays a critical role in delivering value, but also in helping users avoid situations or alert them to something that seems out of the ordinary. No matter what the scenario, as the Foursquare example in the beginning of this chapter illustrated, we have multiple considerations to make when we anticipate a user’s needs and deliver or carry out what we believe the user wants. A good use case for thinking through contextual experiences and products is that of designing a TV-viewing experience across devices. With Netflix being a household name, most of us can relate to some of the considerations we have to make in terms of content recommendations. For instance, there’s often a big difference in what we watch if we watch alone, with a special someone, or with kids.

A few years ago during one of my freelance contracts, I was fortunate enough to work on such a project. One of our tasks was to look at how to best personalize the viewing experience across both live and on-demand content for different viewers. As part of this work, we looked into several aspects that might influence what we showed them. The most obvious ones were as follows:

- Who’s watching?

- What are their viewing preferences?

But in order for us to provide suitable recommendations, we needed to know a bit more:

- Are they watching alone or with someone?

- If they are watching with someone, who are they watching with (e.g., partner, friends, the kids)?

As you start to ask these questions, other questions pop to the surface:

- What day of the week is it (e.g., weekday versus weekend)?

- What time of the day is it (e.g., morning versus evening)?

- Where are they watching?

- What are they watching on?

All of these factors influence what a user might want to watch. But the process doesn’t end there. To truly deliver great recommendations and consider the full context, we need to know even more:

- What did they watch before (e.g., episode in a series or a film)?

- What do we know about their behavior (e.g., what did they start but didn’t finish watching, and why)?

All of this impacts the continuous experience and how to make it easy for the user to pick up from where they left off. However, it doesn’t tell us everything. We also need to know the following:

- What did they think about what they watched before?

- What might they want to watch next?

- How is this influenced by day of the week and time of day and who they are watching with?

- What was the reason for their action, or lack thereof (e.g., why did they stop watching a show or film)?

These were just some of the things that came up during the discovery phase of that project. The list of questions could go on, and rightfully so. Getting these types of experiences right requires digging into the details and embracing the contextual complexity of the products and services that we design.

Embracing the Complexity of Context

As the preceding sections illustrate, there are so many different combinations. To design an experience that is simple, intuitive, and feels as if it knows what the user wants—which is just the kind of experience a user wants when watching video and on-demand content—you need to embrace the complexity and dive straight in. You need to work through what matters step-by-step, what doesn’t, and how it’s all interlinked. The process is complex, but after you’ve worked on figuring out all the different pieces of the product experience, connecting all those detailed parts can be simple. But understanding the context and what will constitute a great experience in different scenarios requires work, including research and talking to people.

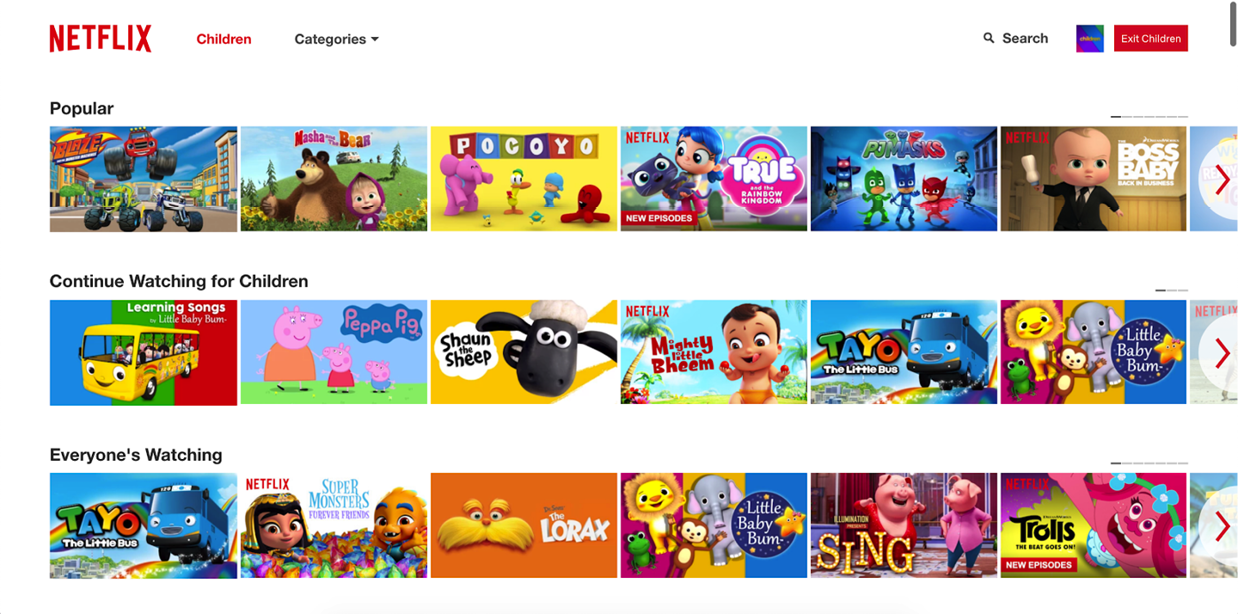

An example that I would not have considered until I myself had a child is that what to recommend next for kids versus for adults is very different. Our daughter, who at the time of this writing is under two years old, wants to watch two shows on Netflix—Peppa Pig and Little Baby Bum. However, even on Netflix’s Children profile, the system works in the same way, meaning that if you finishing watching a show like Peppa Pig, it will disappear from your “Continuously watched” row (Figure 7-3).

For an adult, this is right. You seldom want to watch the same show or film straight after you’ve just finished watching it. For a soon-to-be two-year-old, it’s the exact opposite. The implications of the show automatically disappearing is that when we’re with an impatient toddler who says “Piggu,” as she calls Peppa Pig, on repeat, rather than Piggu being one or a few clicks away, we have to go into search and find it, which takes substantially longer. Netflix will, without a doubt, have multiple reasons for working this way (metrics, ease of build, etc.), but it’s not ideal from our, the users’, point of view.

Figure 7-3

The desktop UI of our Netflix’s Children profile showing the Continue Watching for Children row as the second row

Be it VOD, recommendations through bots, or just general content recommendations, making the right recommendations requires much more than just data. We need to truly understand the context, the relationship, and any value or nonvalue that an interaction has. It’s far too easy to generalize and make assumption-based decisions about what a user does or doesn’t do, but actions don’t necessarily say anything about what users actually value.

In 2016, for example, Facebook changed its newsfeed to show more articles that users actually want to spend time viewing. But getting an understanding of what people want to see wasn’t as easy as it first appeared. Facebook noted:

The actions people take on Facebook—liking, clicking, commenting or sharing a post—don’t always tell us the whole story of what is most meaningful to them. For example, we’ve found that there are stories people don’t like or comment on that they still want to see, such as articles about a serious current event, or sad news from a friend.9

When it comes to analyzing user behavior and providing personalized and tailored experiences, we need to get under the hood in order to understand what drives the user’s action and put it into context.

The Factors and Elements That Make Up Context in Product Design

In traditional storytelling, the context of the story has to do with what story is being told, by whom or what, and how. For product design, context runs along the same lines. It’s about who you’re telling what part of the product story, in what way, when, and where. Depending on the type of product or service, what matters in terms of context will vary.

If you search online, at least at the time of this writing, there is no universal definition of context in design. Ben David defined the building blocks of context as follows:

User context

How people are different

Environmental context

Any physical aspect that influences the application

World context

What is happening elsewhere that may be related to the user

A whole book can (and has been) written on the subject of context—see Understanding Context by Andrew Hinton (O’Reilly, 2014)—so for the purpose of this book, the preceding categorization and a reference to the Understanding Context book will suffice. The key takeaway is that when it comes to product design, context is all about relevance, timing, appropriateness, and value to the person on the receiving end. It requires a deep understanding of who they are and where they are in their journey and own personal story, and how best our product or service can help them.

What Storytelling Teaches Us About Setting and Context

Aristotle, as mentioned in Chapter 2, was the first to point out that the way we tell stories has a profound influence on the human experience of the same. Restrictions of a medium can force a one-size-fits-all approach to the way the story is told. For example, in a book, every word, picture, and paragraph is the same, regardless of who the reader is. Similarly, in film and on TV, the viewer is presented with the same images, sounds, etc., on the screen as all the other viewers. How the readers of the book or the people watching the film or TV program experience it, though, differs.

From what we pay attention to and remember, to what resonates with us, no two people will experience a story in the same way. This all comes down to context—context of who the person is, their likes and dislikes, their backstory, where they’re experiencing it and with whom, etc. The power of a great storyteller lies in the ability to identify and bring these factors to light so that they can be considered in the way that the story is told. This is what the great storytellers back in the Middle Ages were masters at and why being a professional storyteller was so well regarded.

Context in relation to how we tell stories, however, has to do with both the medium and the techniques we use to tell that story, what we include in the actual story (e.g., in terms of backstories, details, etc.) and how we actually tell it, and, of course, the practicalities related to budget, team, equipment, and so on.

When we look at how we tell stories in our day-to-day life—how our day was, what we dreamt about at night, or what we’re thinking about—the approach always differs based on who the story is told to. If we’re talking to close friends, we may share some additional details that we’d leave out if we told the same story to our parents. We often assume a warmer, softer voice when we tell or read a story to a child. And, we’ll jump over or speed up certain bits if part of the group we’re telling a story to has heard it before. Without thinking about it, we’re assessing the situation and the context in which our story is about to be told, and based on our often subconscious assessment, we adapt how we’re telling it so that it’s appropriate for the audience and the situation.

How we tell a story is closely related to what we’re trying to get across with the story and, as Samson suggests, the relationship we want to create with our audience. As we covered in the previous chapter, sometimes a story will be plot driven, and the desire to include particular special effects helps shape it and starts to build up the environment or setting in which the story takes place, as was the case with Rogue One. Other times a particular character drives the plot, and in those instances the context around the character helps inform the story itself and how it’s told, as was the case with Finding Nemo that we referenced in Chapter 5.

Next we’ll look at three areas where product design can draw from traditional storytelling.

Defining Your Setting and Context

Just as it’s crucial to be able to create a shared mental image in everyone’s head of the people we design for, making sure that everyone is on the same page about the setting and context of the product experience is imperative. Often silos between teams and different parts of the organization are due to the individuals not having a shared understanding, or a common language that bridges the gaps and makes the respective parties see the value or importance of what the other party is talking about. Here, using some of the tools from traditional storytelling such as questions to ask, and developing a setting and context chart can be extremely useful, particularly if visualized in the form of a customer experience map.

Creating a World

The power of the word and our imagination lies in the images and the worlds that these create in our heads. My dad often talks about how the books he read to us when we were kids didn’t have that many pictures and, as a result, they sparked our imagination and made us create our own images in our heads of the worlds and characters that he was reading about.

In Chapter 2, I said one of the really distinctive aspects of video games is that the user is immediately immersed into the world of the game. When Pixar story artists talk of a world, what they really mean is the environment or the set of rules in which the story takes place.10

How to go about it

When we talk about product design, worlds can be viewed in different lights. There is the broader world, as in context and setting, in which the product experience resides, but there’s also the world that has to do with branding and other guidelines, such as platform guidelines. These are more in line with the way both game designers and Pixar designers talk of “the set of rules” that govern the world in which the story takes place.

One of the story artists in the Pixar in a Box series says the character should always come first. if you have a blind person forgetting their pants and going to work, she says, that person will have a completely different story than a seeing person forgetting their pants and going to work. The objects and the setting will be the same, but the two characters will have completely different stories. Her colleague, who’s a director, prefers to come at it from the world first and then find the character to go into that world. This is similar to what we experience in product design. We all have different preferences of how to work and the key isn’t so much in which order it happens, but that it does happen. There should always be a bit of back and forth, as one will inform the other. In the Pixar in a Box series references, the story is born when the world and the character meet.

Designing the Set

Though set and setting are different, there is a close connection between them, particularly when we look at them in relation to product design. The setting, as we’ve covered, is all about the time and the place in which a story takes place. Set, on the other hand, is the scenery that is created to help support and tell the story. In some films, like Star Wars and the original Blade Runner, the set itself has become iconic.

For theater as well as film and television, the creation of the set is referred to as scenic design, scenography, stage design, set design, or production design.

How to go about it

The importance of thinking of the setting for product design, and taking it one step further to think of the actual set that has to be designed for each part of the product experience story, has to do with identifying, based on the plot, characters, and the context, what should be present at different parts of the product experience to make sure it all comes together to meet both user and business needs. It’s about identifying both what should be there (and not there) and how to design it, even if it’s something offline and nondigital. And it applies to both the bigger picture as well as the small details. As Evening Standard reported, “A set is more than a backdrop. It can become a storyteller itself, with plot-twisting reveals or intricate attention to detail.”11 With this in mind, it’s important to start planning out the set early on in the product experience discovery and definition phase as, just as in a good story, everything is connected.

Summary

In all good stories, there are key moments when everything just comes together. One of the best things we can do for the people we’re designing for is to fully understand the context. It touches on and influences everything we’ve covered so far. To some extent, combining two words from film, TV, and theater—set and stage—provides a more active and accurate description of the JTBD and the role it plays for planning out and defining the types of product experiences we’re working with.

To fully understand the bigger picture as well as the small details of the experiences we work with, we need to identify all the elements of the set that influence the product or service experience. Then we need to stage that experience in light of what we know about the users, other characters, and actors, and the different contexts in which the experience takes place, so that it all comes together and we deliver against it.

No matter how simple the experience might be (and even if we’re just designing a landing page), being more explicit and including set design and staging as part of our work helps ensure that we have a good foundation when we start defining our content strategy and information architecture and the steps that come after that.

Increasingly, as offline and online blend and influence each other, we need to ensure that we understand the world in which the people live who will come across and use our products or services.

Setting and context form a big part of the experience narrative. They influence not only how our users will experience our product or service, but also what and how we should tell our story to make sure it comes together. It’s by thinking through the context in which people will use our product and services that scenarios are born. Then we’re able to really start visualizing and adding detail to the narrative that surrounds the use of our product and service; our imagination is sparked. And, if we really listen, the story will start to tell itself. Next, we’ll look at how to use storyboarding to help visualize and aid this process.

1 Courtney Carpenter, “Discover the Basic Elements of Setting in a Story,” Writer’s Digest, May 2, 2012, https://oreil.ly/QGxrg.

2 Julien Samson, “Why Context Matters In Writing,” Medium, June 28, 2017, https://oreil.ly/8Ekoi.

3 Ami Ben David, “Context Design: How to Anticipate Users’ Needs Before They’re Needed,” The Next Web, April 28, 2014, https://oreil.ly/_jZOi.

4 Albrecht Schmidt, “Context-Aware Computing,” The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd Edition, https://oreil.ly/Y2raZ.

5 Tutti Taygerly, “Designing Big Data for Humans,” UX Magazine, June 24, 2014, https://oreil.ly/m2MtW.

6 Larry Page, “Where’s Google Going Next?” TED2014 Video, March 2014, https://oreil.ly/aRfqG.

7 From: Norman, D. A. (2002). Emotion and design: Attractive things work better. Interactions Magazine, ix (4), 36-42.

8 Page Laubheimer, “Distracted Driving: UX’s Responsibility to Do No Harm,” Nielsen Norman Group, June 24, 2018, https://oreil.ly/rJ_TW.

9 Moshe Blank and Jie Xu, “More Articles You Want to Spend Time Viewing,” Facebook, April 21, 2016, https://oreil.ly/mDwSW.

10 “Your Unique Perspective,” Khan Academy, https://oreil.ly/gimne.

11 Zoe Paskett, “London Theater,” Evening Standard, February 15, 2019, https://oreil.ly/ho5U-.